Last week, the unexpected

deluge of exciting news from Romania kept me extremely busy. I cannot be happier with Nobu's great successes, and, as a long-time fan, I am proud of the marks that he has made in yet another corner of the world.

![]()

There is, however, one sore spot that I held off mentioning in my too-many postings.

The culprit is

an article posted on Napoca News, penned by Grid Modorcea, Ph.D in Arts.

I don't believe that in his piece, the author, Dr. Modorcea, meant any disrespect to Nobu, but the essay somehow managed to hit all the

wrong notes for me.

Below I will make my case. You be the judge as to whether my ire is justified. The full text of the article, with an English translation, can be found at the bottom of this page.

Wonderful Children of music

The piece annoys me from the get-go. Starting with the title and a lengthy opening paragraph that begins with "Even a brief overview of the history of music immediately highlights the fact that music is the art that has produced the largest number of miraculous children, that is, early talents, who then proved their genius throughout their career."

All that, so the author can lump some of the notable artists that appeared in the first week of the Enescu Festival under the broad umbrella of

Copii-minune ai muzicii -- Wonderful Children of music:

"Denis Matsuev, ... Elisabeth Leonskaja, Evgeny Kissin, Maxim Vengerov, Yuja Wang , Julia Fischer ..." He eventually names Nobu. More on this later."E un fel de Andrea Bocelli al pianului"

No sooner has he brought up Nobu than the author springs this line on us: "E un fel de Andrea Bocelli al pianului" [He is kind of the Andrea Bocelli of pianists.] Bocelli, born 1958 reportedly with congenital glaucoma, is a blind Italian opera singer. He has a worldwide following, complete with best-selling record albums and sold-out concerts. With all due respect to Mr. Bocelli, I submit that excelling in classical piano playing without the benefit of sight is a challenge several notches above what it takes to sing moderately well without sight. Furthermore, Nobu -- born blind -- has never been able to see the instrument nor the music scores that he plays, while Mr. Bocelli had sight until age 12. But what set me off the most is perhaps that the line dredged up painful memories of an infamous article published by the Wall Street Journey days after Nobu's 2009 Cliburn win, in which writer Benjamin Ivry wrote "Many articles have focused on the fact that Mr. Tsujii was born blind and learns music by ear. But only results count ... Promoters can easily turn musical performances into stunts, like the staged operahouse appearances of the otherwise cannily intelligent tenor Andrea Bocelli."

Ten years later, reading those stinging words still makes me want to give the churlish writer a good kick that he so deserves. Trust me, Mr. Ivry: Nobu's performances are decidedly NOT staged stunts; perhaps you should try to see him perform in a concert, to see for yourself. ![]()

Nobu l-a japonizat cu finețuri tipice artei japoneze"

You will find that line near the end of the piece. It translates to

"Nobu has Japanesecized it [Rach 2] with typical Japanese artistry. " This is what Dr. Modorcea wrote:[Translated from Romanian] Here, at the festival, Nobu Tsujii played Rachmaninov's Concert no. 2 with the Youth Orchestra and conductor Michael Sanderling. The concerto is the most popular piano work in the world, a true symphonic standard, emblematic of the universalized Slavic soul, which Nobu has

Japanesecized with typical Japanese artistry. As

[Akira] Kurosawa [filmmaker] once, through

Rashomon, Europeanized Japanese mythology. It is an attribute of a genius to make bridges between cultures."

In plain language, Dr. Modorcea accuses Nobu of making Rach 2 sound Japanese.

The horror! Perish the thought! Unlike some pianists who take liberty with interpreting what they play, Nobuyuki Tsujii (yes, a genius -- he got that right) has the utmost respect for the composers and takes great pain to stay true to each composition that he performs. In documentaries aired in Japan, he has been shown traveling to homes of Chopin, Rachmaninov, Wagner, etc. to -- in his own words -- get a sense of the composer's life to allow him to interpret their works more faithfully. Nobu would surely consider it sacrilegious to "

japonizat" a masterpiece of Rachmainoff, as this author suggests! Totul este un spectacol la ea...

Of the wunderkind turned big-time performers at the Enescu Festival last week, the author spent the most ink on Ms. Yuja Wang and in turn Nobu. My eyebrows went up when I saw their names juxtaposed in this piece. (Ms. Wang performed on Sept 8 in Bucharest, two days before Nobu's concert on Sept 10. Nobu, accompanied by his manager(s), was actually in the audience at her concert.)

I make no secret that I am not a fan of Ms. Wang, because I consider her distasteful attires on stage an affront. But I am well aware that she is currently the tempest -- or temptress rather -- in the teapot of classical music, a major box-office draw who can be counted on to sell out the big concert halls. The author of this article, doctorate and all, is yet another scholar who seems to find her irresistible, heaping praise on her "demonic playing" and "flamboyance" and "beauty," complete with tiresome description of her provocative stage garbs and mannerisms.

By all accounts, Ms. Wang has piano chops to spare. I accept that. Why then, does she debase herself with dressing like, as one Japanese Twitter put it, a Ginza hostess? I do commend the author for this succinct line: "Totul este un spectacol la ea, dincolo de abilitățile pianistice [Everything is a show for her, beyond the piano skills." Okay, glitz sells, especially when conflated with exhibitionism. I will grudgingly resign to what some people suggest, that she is good for classical music, bringing in audience. But to me, her entire facade smacks of artificiality. Everything is made up -- heavy cosmetics, underwear that passes for costume, spiky heels. Beauty is in the eye of the beholders.

Instead of lumping them together as "wonderful children of music," I think a more meaningful angle, for Dr. Modorcea's essay, would have been that Ms. Wang, is -- as he put it so aptly -- all about show business, while Mr. Tsujii, devoid of vanity because of his congenital blindness, is what we in America call true grit: real courage and true effort -- with no assist from deceptive cosmetics and provocative costumes. He rocks his body; his bow-tie goes askew; he has to be guided on and off stage. If Ms. Wang is all about show business, Mr. Tsujii is the embodiment of unvarnished honesty.

Glitz sells. Money talks. I know who (outside of Japan) is considered a bigger name for concert tickets. But I know which of these two "wonderful children of music" has my RESPECT.

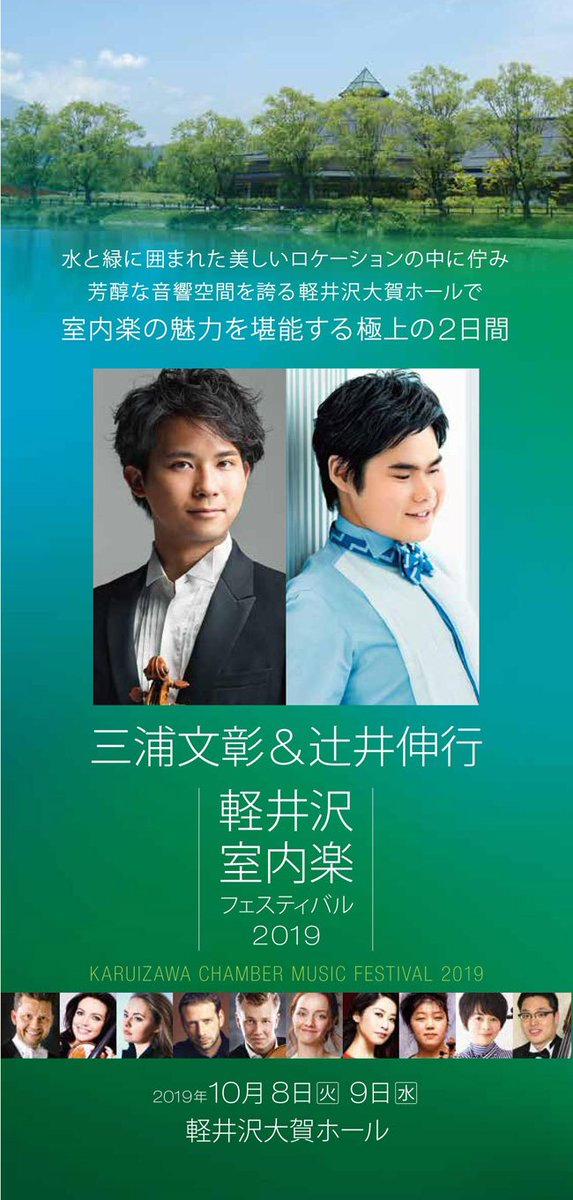

Image below:

Shutterstock photo captures Nobu in tears at the end of performing Rachmaninov's Piano Concerto no. 2 with the Romanian Youth Orchestra on September 10.

![]()

***

Below is the original Romanian text and an English translation by Google Translate. The photo is presumably that of the author, Grid Modorcea, Ph.D in Arts.

![]()

Copii-minune ai muzicii

O privire chiar și sumară asupra istoriei muzicii, scoate imediat în evidență faptul că muzica este arta care a dat cei mai numeroși copii-minune, adică talente precoce, care și-au dovedit apoi geniul pe parcursul carierei. Ce geniu nu a fost preecoce în muzică? Bach? Mahler? Ceaikoveki? Gândiți-vă la orice mare compozitor sau instrumentist și veți descoperi în biografia lui precocitatea geniului.

În alte arte, cum este literatura, de multe ori geniul nu apare în copilărie, mulți scriitori descoperindu-și târziu vocația. Dar în muzică este altceva. Fiindcă muzica nu are granițe de limbă, nu are granițe de nici un fel. Ciobanul cu fluierul său este universal. Sigur, pentru a păși pe calea muzicii culte, căci despre ea este vorba aici, e nevoie de puțină carte, în primul rând trebuie să știi să citești notele muzicale, altfel „vei păzi porcii”, așa cum i-a spus lui Jorjac tatăl său, după ce l-a dus la Eduard Caudella, să-l asculte. Povestea este foarte interesantă și o redă Enescu amănunțit în Amintirile sale. Jorjac, deși avea 5 ani, l-a pus pe Caudella să-i cânte la vioară, fiindcă la acea vârstă el nu mai avea ce învăța de la Lae Chioru, lăutarul, primul său profesor. De altfel, la 5 ani, Enescu a compus prima lucrare simfonică, un concert de pian și vioară, pe care l-a numit „Țara Românească”, desnând în loc de note gândaci, furnici, frunze, ce vedea în grădina casei, acolo unde și-a confecționat și o vioară dintr-un cocean de porumb. Iar la 7 ani, când a revenit la Iași, Caudella le-a spus părinților săi că nu are ce să-l mai învețe, să-l ducă mai departe, la Viena. Și miracolul a continuat, prin lecțiile vieneze, pe care le-a consemnat elevul Enescu într-un jurnal, unde dă note marilor maeștri ai muzicii și maeștrilor vienezi ai timpului.

Nu întâmplator miezul inspirației, ca și al ideilor sale mari, îl descoperim în piesele de tinerețe. Atunci geniul precoce al lui Enescu s-a manifestat în toată vigoarea (iuțirea de sine).

Lista cu genii precoce ai muzicii este nesfârșită. Italienii, germanii și rușii ne-au copleșit cu asemenea fenomene, culminând cu Vivaldi, Mozart, Schumann sau Rahmaninov, și cu toți titanii lumii. Ba ne întrebăm, cine nu a fost copil-minune în muzică? Este în afară de orice discuție că mulți oameni se nasc cu geniul muzicii în ei. Mi-aduc aminte când a venit la București și a cântat la Festivalul „Enescu” pianistul american Van Cliburn, a fost primit ca un copil-minune, un fenomen, care, la 23 de ani, cucerise premiul I la Moscova, la Festivalul „Ceaikovski”, în plină realitate bolșevică, dar muzica a dovedit că e mai presus decât blocul socialist!

Numai la această ediție a Festivalului „Enescu”, pe care o comentăm acum, au fost prezenți o ceată de copii-minune, pe lângă Denis Matsuev, comentat anterior, să-i trecem pe Elisabeth Leonskaja, Evgeny Kissin, Maxim Vengerov, Yuja Wang, Julia Fischer, poate și pe românii Mihaela Martin, Alexandra Dariescu, Daniel Ciobanu, Alexandra Silocea, deși în fesvial nu prea ne-au convins. Dar n-o uit pe pianista Luiza Borac, cea mai bună interpretă a sonatrelor lui Enescu. Și sunt mulți, foarte mulți. Calitatea de copil-minune nu mai este o excepție, în muzică este un fenomen curent, natural.

Pianista rusă Elisabeth Leonskaja este la Festivalul „Enescu” ca la ea acasă, de când avea 18 de ani și a câștigat la ediția din 1964 premiul I la Concursul Festivalului, secțiunea pian, moment pe care ea îl consideră definitoriu pentru cariera sa. De atunci a revenit de nenumararte ori, aproape la fiecare nouă ediție.

Acum, în compania Orchestrei Simfonice a Radiodifuziunii din Viena, a cântat „Imperialul”, Concertul nr. 5 pentru pian și orchestră de Beethoven, un emblematic șlagăr simfonic, o bijuterie armonică, poate cea mai senină și optimistă lucrare a lui Beethoven, foarte contabilă, având un fermecător suflu melodic. Orchestra din Viena a interpretat și Bolero de Ravel, alt copil-minune, poate cel mai popular șlagăr simfonic, dar pe care l-a abordat superficial, total neinspirat, fiindcă a marcat redundanța tonală a nucleului melodic, foarte iberic, așa cum l-a dorit Ida Rubinstein, balerina care a comandat această lucrare de balet. Șlagărele simfonice, dacă nu sunt cântate la perfecțiune, își trădează părțile slabe, în special schematismul construcției.

Șlagăr simfonic a fost și Simfonia a II-a de Brahms, cântată de Capela de Stat din Dresda, una dintre cele mai vechi orchestre din lume (1548), dirijor sud-coreanul Myung-Whun Chung. Înfijnțată ca o orchestră de curte, princiară, capela a avut parte de aportul dirijoral al unor faimoși compozitori, precum Carl Maria von Weber și Richard Wagner.

Dar regalul serii s-a numit Yuja Wang, una dintre cele mai flamboaiante și prodigioase pianiste din tânăra generație, invitată și aclamată pe marile scene din întreaga lume, pe care am văzut-o și la New York, la Carnegie Hall, cântând chiar același Concert nr. 3 pentru pian și orchestră de Serghei Rahmaninov. Evident, acolo n-a fost atât de aclamată ca la București, unde a fost încărcată de flori și a oferit trei bisuri. Publicul românesc este foarte generos cu copiii-minune, iar Yuja este un copil-minune, este și frumoasă, un fel de Sharapova a muzicii simfonice. Ea apare ca o divă hollywoodiană, în costume foarte sexy. La o ediție anterioară, avea o rochie roșie despicată, până la dresuri, iar acum una albă, transparentă, care îi punea și mai puternic în evidență corpul, formele lui senzuale.

Cântă demonic și cultivă aspectul carismatic. Este ciudată și prin felul epatant cum salută publicul, înclinându-se până la pământ, apoi zvâcnind în sus, zburlindu-și părul scurt, ca un cimpanzeu furios. Totul este un spectacol la ea, dincolo de abilitățile pianistice. Yuja este de altfel singura pianistă care, după știința noastră, cântă și Concertul nr. 2 de Prokofiev, fiind în aceeași undă nebună cu Matsuev. Ea atacă cu curaj tot ce este dificil în pianistica mondială, cum sunt și studiile lui Skriabin. Așa este și Concertul nr. 3 de Rahmaninov. Care este categoric pătruns de un suflu romantic, care i-a dat aripi pianistei, ea reușind să transmită un amestec sui-genris, oscilând între stări de mare gingășie pianistică și de forță cromatică, dovedind o dexteritate de invidiat, etalon de virtuozitate, model de iuțire de sine.

Desigur, Rahmaninov nu are tăieturile lui Prokofiev, inventivitatea lui absolută, rupturile categorice cu tradiția, dar poate fi considerat din aceeași familie calitativă.

Copil-minune este și pianistul japonez Nobuyuki Tsujii, care s-a născut orb, dar are geniu muzical, uimindu-i pe toți cunoscătorii pentru capacitatcea lui de a învăța și cânta muzică după ureche. E un fel de Andrea Bocelli al pianului. I-a uimit pe specialiști, cântând una dintre cele mai dificile piese de Beethoven, Sonata nr. 29 (de o oră), fără cusur. Miracolul dumnezeiesc face posibile lucruri de neconceput.

Nobu Tsujii este și un compozitor de mare talent. El compune multă muzică de film, creațiile sale ilustrând numeroase filmele japoneze de succes. În 2011, compozițiile sale i-au adus marele premiu al Japonia Film Critics Award. Nobu este foarte iubit în Japonia. Marea campioană japoneză de patinaj artistic, Midori Ito, duce faima lui Nobu și imensa lui sensibilitate și în lumea sportului, patinând în cadrul unui eveniment mondial (Master Elite Oberstdorf 2011) pe muzica lui, „Whisper of the River”.

Marele pianist Van Cliburn a afirmat într-un interviu acordat după recitalul de debut al lui Tsujii la Carnegie Hall (în noiembrie 2011): „Ce emoție să auzi acest pianist genial, foarte talentat, fabulos. Am simțit prezența lui Dumnezeu în sală, atunci când a cântat. Sufletul său este atât de pur! Iar muzica lui este atât de minunată, încât poate să urce la infinit, până la cel mai înalt cer”.

Aici, la festival, Nobu Tsujii a cântat Concertul nr. 2 pentru pian și orchestră de Rahmaninov cu Orchestra de tineret, dirijor Michael Sanderling. Concertul este cea mai popular piesă de pian din lume, un adevărat șlagăr simfonc, emblematic pentru sufletul slav, universalizat, pe care Nobu l-a japonizat cu finețuri tipice artei japoneze. Așa cum odinioară Kurosawa, prin Rashomon, a europenizat mitologia japoneză. E un apanaj al geniului să facă punți între culturi.

Grid Modorcea, Dr. în arte

----------------

Tranlation by Google

Wonderful children of music

An even brief overview of the history of music immediately highlights the fact that music is the art that has given the most miraculous children, that is, early talents, who then proved their genius throughout their career. What genius was not early in music? Bach? Mahler? Ceaikoveki? Think of any great composer or instrumentalist and you will discover in his biography the precocity of genius.

In other arts, such as literature, genius often does not appear in childhood, with many writers discovering their vocation late. But there is something else in music. Because music has no language borders, it has no borders of any kind. The shepherd with his whistle is universal. Of course, to walk the path of cult music, because it is about here, you need a little book, first of all you need to know how to read the musical notes, otherwise "you will keep the pigs", as Jorjac told his father, after taking him to Eduard Caudella, to listen to him. The story is very interesting and Enescu plays it in detail in his Memories. Jorjac, although he was 5 years old, had Caudella play the violin, because at that age he no longer had to learn from Lae Chioru, the jeweler, his first teacher. In fact, at the age of 5, Enescu composed the first symphonic work, a concert of piano and violin, which he called "Romanian Country", waking up instead of notes cockroaches, ants, leaves, which he saw in the garden of the house, where he made and a violin from a corn cocaine. And at the age of 7, when he returned to Iasi, Caudella told his parents he had nothing to teach him, to take him further to Vienna. And the miracle continued, through the Viennese lessons, recorded by the student Enescu in a journal, where he gives notes to the great masters of music and the Viennese masters of the time.

It is not by chance that the core of inspiration, as with his great ideas, is found in the pieces of youth. Then Enescu's early genius manifested itself in full force (self-condemnation).

The list of early geniuses of music is endless. The Italians, the Germans and the Russians overwhelmed us with such phenomena, culminating with Vivaldi, Mozart, Schumann or Rahmaninov, and with all the titans of the world. We wonder, who hasn't been a wonderful kid in music? It is apart from any discussion that many people are born with the genius of music in them. I remember when he came to Bucharest and sang at the Festival "Enescu" the American pianist Van Cliburn, was received as a miracle child, a phenomenon that, at 23 years, had won the first prize in Moscow, at the Festival " Tchaikovsky ”, in full Bolshevik reality, but the music proved to be above the socialist bloc!

Only at this edition of the "Enescu" Festival, which we are commenting on now, were there a wonderful children's party, besides Denis Matsuev, previously mentioned, to pass Elisabeth Leonskaja, Evgeny Kissin, Maxim Vengerov, Yuja Wang , Julia Fischer, maybe the Romanians Mihaela Martin, Alexandra Dariescu, Daniel Ciobanu, Alexandra Silocea, although in fesvial we were not convinced. But I do not forget the pianist Luiza Borac, the best performer of Enescu's sonatas. And there are many, many. The quality of child-wonder is no longer an exception, in music it is a current, natural phenomenon.

Russian pianist Elisabeth Leonskaja has been at the "Enescu" Festival as at home, since she was 18 years old and has won at the 1964 edition the 1st prize at the Festival Contest, the piano section, a moment that she considers to be defining for her career. Since then, he has come back countless times, almost every new edition.

Now, in the company of the Vienna Radio Broadcasting Symphony Orchestra, he sang "Imperial", Concert no. 5 for Beethoven's piano and orchestra, an iconic symphonic chorus, a harmonic gem, perhaps Beethoven's most serene and optimistic work, very accounting, having a charming melodic blast. The Vienna Orchestra also performed Bolero de Ravel, another child-wonder, perhaps the most popular symphonic chorus, but he approached it superficially, totally uninspired, because it marked the tonal redundancy of the very Iberian melodic core, as Ida Rubinstein wanted. , the ballerina who commissioned this ballet work. The symphonic praises, if not sung to perfection, betray their weak parts, especially the schematic construction.

The symphony was also the Second Brahms Symphony, sung by the Dresden State Chapel, one of the oldest orchestras in the world (1548), South Korean conductor Myung-Whun Chung. Set up as a court orchestra, a prince, the chapel was part of the conducting contribution of famous composers, such as Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner.

But the gift of the evening was called Yuja Wang, one of the most flamboyant and prodigious pianists of the young generation, invited and acclaimed on the big stages around the world, which we also saw in New York, at Carnegie Hall, singing even the same Concert no. . 3 for piano and orchestra by Sergei Rahmaninov. Obviously, there she was not as acclaimed as in Bucharest, where she was loaded with flowers and offered three bows. The Romanian public is very generous with wonderful children, and Yuja is a wonderful child, she is also beautiful, a kind of Sharapova of symphonic music. She looks like a Hollywood diva in very sexy costumes. In a previous edition, he had a red dress split up to the tights, and now a white, transparent, which made his body even more powerful, his sensual forms.

He sings demonic and cultivates the charismatic aspect. It is strange, too, in the way he is greeted by the audience, bending to the ground, then fluttering upward, ruffling his short hair like an angry chimpanzee. Everything is a show for her, beyond the piano skills. Yuja is also the only pianist who, according to our science, sings Concert no. 2 by Prokofiev, being in the same crazy wave with Matsuev. She bravely attacks everything that is difficult in world pianism, such as Skriabin's studies. This is how Concert no. 3 by Rahmaninov. Which is definitely penetrated by a romantic soul, which gave the pianist wings, she managed to transmit a sui-genris mixture, oscillating between states of great pianistic tenderness and chromatic force, proving a dexterity of envy, a standard of virtuosity, a model of jerking. self.

Of course, Rahmaninov does not have Prokofiev's cuts, his absolute inventiveness, his categorical breaks with tradition, but he can be considered from the same qualitative family.

The child-wonder is also the Japanese pianist Nobuyuki Tsujii, who was born blind, but has musical genius, astonishing all connoisseurs for his ability to learn and sing music by ear. It's kind of Andrea Bocelli's piano. It amazed the specialists, singing one of Beethoven's most difficult pieces, Sonata no. 29 (one hour), seamless. The divine miracle makes things unthinkable possible.

Nobu Tsujii is also a very talented composer. He composes a lot of film music, his creations illustrating many successful Japanese films. In 2011, his compositions brought him the Japan Film Critics Award. Nobu is very loved in Japan. The great Japanese figure skating champion, Midori Ito, carries Nobu's fame and immense sensitivity in the world of sport, skating at a world event (Master Elite Oberstdorf 2011) on his music, "Whisper of the River".

Grand pianist Van Cliburn said in an interview after Tsujii's debut recital at Carnegie Hall (in November 2011): “What a thrill to hear this great, very talented, fabulous pianist. I felt the presence of God in the room when he sang. His soul is so pure! And his music is so wonderful that it can go up to infinity, to the highest heaven. ”

Here, at the festival, Nobu Tsujii sang Concert no. 2 for Rahmaninov's piano and orchestra with the Youth Orchestra, conductor Michael Sanderling. The concert is the most popular piano piece in the world, a true symphonic bass, emblematic of the universalized Slavic soul, which Nobu has Japaneseised with typical Japanese art. As Kurosawa once, through Rashomon, Europeanized Japanese mythology. It is an apology of genius to make bridges between cultures.

Grid Modorcea, PhD in arts

RELATED ARTICLESNobuyuki Tsujii in Romania September 2019